The Venetians, for example. They decreed that the Delta was theirs. They came from the sea to fall upon Comacchio and its rich swamps: rich not only in eels, but also in salt. With the salt, the eels, and marinated fish, the folk of Comacchio used to set off on board their big barges to sail up the Po. They navigated as far as Pavia, perhaps even Milan, and they sold their wares.

The Estes were the first to dominate them. Then the Venetians, who had will cut the Po in 1604 to divert it away from Venice, sent in their corsairs to rob, plunder, and put houses and warehouses to town. Thus began the centuries of overty. The folk of the Delta were left with the eels, but not even these were their property.

The eels. For centuries, it seems that Comacchio and the Delta had nothing else offer any visitors. Writers and authors of travelogues had little to say about the place, save for the eels.

In Sodom and Gomorra, Curzio Malaparte imagines that the politics of Comacchio aimed "TO make ALL OF Emilia an immense lagoon AND TO breed eels ALL the way TO the walls OF Bologna". The bizarre eccentric, Vittorio G. Rossi, one of the greatest Italian journalists of this century, came to this place to find out how and why eels must cross the ocean in order to mate: «I have never heard of anyone who was not an eel who has had to go on such a long honeymoon voyage».

I think it's a fine thing that someone was curious enough to want to know why a fish chooses to abandon a quiet pool to cross the ocean and mate in the Sargasso sea, but I don't understand why these poets and writers of Comacchio are interested in little else apart from the eels. Perhaps it is because, as G. Rossi adds, «poets, even those who sing of things ethereal, are really more interested in a good plate of pasta».

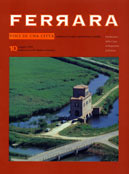

Torre Abate was built a stone's throw from Bosco della Mesola, in the centre of which there is a clearing, a species of navel in which no tree grows. A star once fell here, the local legend says, Here, two young lovers consumed their forbidden passion and were killed, locked in each other's arms, and their blood, spilled all around, ensured that no plant, no blade of grass, would grow for centuries after.

I prefer this version, forbidden love is the salt at history's banquet. It was the desire to talk of forbidden love that drew the great writer and director Mario Soldati to the Delta. There he made a film with Sophia Loren, La donna del fiume.

I watch the ripples on the water surrounding the reed beds below Torre Abate. I am more convinced than ever: all you have to do is look. Nearby, at Goro, the clam beds have brought prosperity to the people, radically changing their lives. But Torre Abate remains, the solitary guardian of other stories, other philosophies. As the sea gradually withdrew, it became the cement of an ancient memory. They tell me that, before the tower was built, this place was called Porto Abà. So there was a harbour and, perhaps, a lighthouse. The abbot's lighthouse. Which abbot? No one knows. An abbot, who came here in order to pray and seek tranquillity and meditation? No one knows. Don't look for answers, the salty wind from the sea seems to say.

The first time I came here, it was a crisp, cold spring day and I wanted to write a verse or two: the solitude and the mysterious whisperings of nature give rise to such strange ideas. I re-read the slip of paper, then I did as I have seen people do in Buddhist temples in the Orient: you take a little prayer written on a piece of paper, then you place it in the brazier at the entrance to the temple and let it burn: if the ashes fly upwards, then it means that God has accepted the prayer; if they do not, then it's your problem. I burned my four stupid and rhetorical verses. I watched. The wind took the ashes and carried them off, on the trail of the birds of passage. I saw them disappear over the horizon. That's poetry for you, I said to myself.