with particular attention to his much-loved Ferrara. In addition to numerous articles, he also published La Nazione ebraica spagnola e portoghese negli Stati Estensi (Rimini, Luisé Ed., 1992) e The Hebrew Portuguese Nations in Antwerp and London at the time of Charles V and Henry VIII. New documents and interpretations (New Jersey, Ktav Publishing Company, 2004).

with particular attention to his much-loved Ferrara. In addition to numerous articles, he also published La Nazione ebraica spagnola e portoghese negli Stati Estensi (Rimini, Luisé Ed., 1992) e The Hebrew Portuguese Nations in Antwerp and London at the time of Charles V and Henry VIII. New documents and interpretations (New Jersey, Ktav Publishing Company, 2004).

His passion for history was not attained through academic studies, but was the result of a tendency to piety, or respect for the tradition and history of his ancestors and his own Sephardic origins, his inexhaustible desire to re-establish truth based on memory. This book is the opus  magnum, the conclusion of a life plan and the restoration of an historical event to the dignity of memory.

magnum, the conclusion of a life plan and the restoration of an historical event to the dignity of memory.

What does this book tell us and what is its purpose? In the same year that the American continent was discovered, for political and religious reasons, the kingdoms of Spain decided to expel the Jews from their lands. The ships departed from ports in Spain and then from Lusitania, carrying this unwelcome cargo of pain, reminding us of the present-day where other desperate people undertake journeys looking for a safe haven. The ships stopped at Genoa, where the 'outcasts of the earth' were prevented from landing. But a representative of the Este court in Ferrara, under Ercole d'Este I, was sent offering "tolerance" to the Jews. They were invited to Ferrara to work - not with guarantees of servitude, but with some form of autonomy to protect them against the ruthless rules  of the Church, and to exercise those professions in which Jews had somehow become specialists: weaving fabrics, manufacturing precious gems and metals, changing currency. A "nation" was born in Ferrara giving an identity to a community that had the same need to belong as a people.

of the Church, and to exercise those professions in which Jews had somehow become specialists: weaving fabrics, manufacturing precious gems and metals, changing currency. A "nation" was born in Ferrara giving an identity to a community that had the same need to belong as a people.

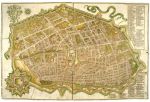

In 2002, during the Italian Presidency of the EU, Ferrara was chosen as a representative of a "unique" renaissance, highlighted in the exhibition in Ferrara Castle the following year. Here we saw the exceptionality of the political-cultural proposals made by the Este dynasty during the period of its greatest splendour.

This "unique" Este plan allowed the Sephardic Jews (but also the Ashkenazi and Italian Jews) in Ferrara to find not the heimat (the homeland of the heart), but the 'permission', which, starting from "tolerance", justifies the ways and opportunities for political structures to access the status of "nation", or organized group, and to be welcomed in the city, defended by the Duke's policy, protected as much as possible against the refusal to accept them that was demonstrated by the whole of the rest of Europe.

As a result of these fundamental contributions the Renaissance singulière, shown in the 2002 exhibition, became a Renaissance that was different, if not unique, in a long period of political and ideological decisions.

In his wonderful introduction to the two volumes of the book, Adriano Propseri warns that Aron Leoni's aim was to provide evidence of something that was missing: the absence of Jews in public life. The desire to erase this role created a memory gap that the book, and the documents it so passionately researched, wants to fill, thus limiting the damage of the loss. Prosperi insists on this concept, i.e. that the curtailment suffered by Jews in public life has been weighing on our collective conscience by formulating a pressing question: would, over time, Italian history have been different if the Ferrara model had been adopted? History is not made with hypothesis but with facts, but it is also true that historical thinking can reason and find the opening in the net that surrounds us and prevents us from escaping from the consequences of the historical "facts".

The second volume is told as a story in the literary sense, based on a framework that could be read as follows: the painstaking recovery of evidence linked to the progressive roots in Ferrara of the Jewish "nations", from the Sephardic to the Ashkenazi, from the "Italian" Jews to the "Marrani" and conversos, in continuous correlation with the strategy of Ercole I, Alfonso I and, above all, Ercole II d'Este.

The volume also describes the events of the most important Jewish families who settled in Ferrara: the Abravanel family, the Mendes-Benveniste de Luna Naci family or Enriques Benveniste; the Italians and Germans who established themselves in Ferrara and flourished and prospered, also benefiting the dynasty that defended and saved them, at least until the death of Ercole II, from the encroachments of the Church.

An important chapter is dedicated to Jewish publishing activities in Ferrara, including masterpieces such as the Biblia Espanola, or the first Castilian translation of Petrarch's Canzoniere. Another of these fascinating tales is that of Beatrice de Luna alias Grazia Naci or Nasi, a complicated story of this banker who, through intelligence and ability, managed to accumulate one of the largest fortunes in Europe and to administer it, for a certain period of time, in Ferrara.

Leoni adds careful observations to the story about the Este family and their policies, especially those of Ercole II who, when faced with the harshest attacks and pressures from the Church, not only protected the Jews, but allowed them to create «a centre of Jewish study open to believers of any faith».

In 1556 the pope accused the Jews of unlawful activity and imposed a new tax. Ercole defended them, explaining to the pope how important these people, including the Marranos, were for the state's economy. Ercole, together with the entire Este family, was a man of his time but the unheard of novelty for that period was his outspoken defence of the Jews. A policy that probably anticipated the tragic end of the Este power in Ferrara, with the devolution of the city sanctioned by the Papal States in 1598. The epilogue details the experiment in Ferrara, which stood out against the widespread European desire to rule over the Jewish "nations" - the consequences of which are still tragically evident to the present day. Although Alfonso II reconfirmed all the safe-conducts and privileges, in 1570 the infamous yellow insignia was imposed and, in 1581, a group of Portuguese men accused of conversion to the Jewish faith were arrested under the orders of the Duke. The following year the privileges were restored until devolution. The Nations were no longer called Spanish and Portuguese, but Spanish and Levantine.