Palazzo Massari

L'ampia struttura di Palazzo Massari ospita:

- Museo Giovanni Boldini

- Museo dell'Ottocento

- Museo d'Arte Moderna e Contemporanea Filippo De Pisis

- PAC Padiglione d'Arte Contemporanea

Il parco Massari è aperto al pubblico.

Mystery and blades of grass in Filippo De Pisis

The re-emergence of the herbarium collected by the Ferrara painter as a young man.

The re-emergence of the herbarium collected by the Ferrara painter as a young man.

The artistic sensibility of many leading cultural figures was cultivated by collecting grasses, herbs and flowers stalks, to then smoothen them out and press them between sheets of blotting paper:Obviously the great naturalists were enthusiasts, but world-famous thinkers also shared this hobby (Rousseau,Goethe,von Chamisso and Hesse), as well as poets,

Boldini in Paris

The relationship between Boldini and French Impressionism will be explored in this great exhibition.

The relationship between Boldini and French Impressionism will be explored in this great exhibition.

Boldini painted a fascinating picture called Cantante mondana [“Society singer”] in the mid-1880s. It shows a snapshot of the Paris of the late nineteen-hundreds - the life, the cafés and the music halls that the artist patronised along with his friends and fellow-painters like Degas - and as such lay outside the area for which he was renowned, namely portrait painting.

The Knigts of Malta in Ferrara

The Order honors the city that welcomed it with a philatelic emission.

Which are the historical reasons that determined the choice of Ferrara, decided by pope Leone XII, to protect the Order from the greed of those who aimed to confiscate its assets, as the French and English did after the occupation of the island of Malta? The government of Naples from which Catania depended, had declared, without any authority, the abolition of the Order, while the empire of Austria had assumed the protection of the Order. Therefore, Rome favored a center that, although belonging to the Papal State, accommodated an Austrian garrison and moreover was not too distant from the Hasbugical border. Therefore, protected and welcomed with the deserved dignity in the city of Ferrara, the jerusolimitan knights gave the start, as Ostoja wrote, “to a singular mirabile spiritual sovereignty and an organization that would have allowed the continuation of those superb activities in hospitality that the Order had begun since the XI century in Jerusalem.”

Lost the island of Malta, the knights were compelled to migrare, at first to Catania, then to Ferrara where they remained for eight years until 1834. In the 1826 the Liutenant of the Order, Frà Antonio Busca, Marquis of Lamagna (1767-1834) reached Ferrara with the knights Angelo Ghislieri from Jesi and Alessandro Borgia from Velletri. Welcomed by Cardinal Tommaso Arezzo, Legacy of Ferrara and already Nunzio near the Zar of Russia (we remember that Czar Paul I had been made Great Master of the Order, although of orthodox religion), the knights took lodging in the Palazzo Bevilacqua (later Massari) where they implanted the papal chancery and they carried out their action with the spirit who had animated them for centuries in the defense of the Christian faith. Cardinal Arezzo offered the knights the church and the ancient Canonical convent of the Lateranensi: a temple in the form of Greek cross, dedicated to San Giovanni Battista, rich with works of art. The honor made to Ferrara for the residence of the Order that, after the Napoleonic storm was being reconstituted, was not forgotten after that the Priore di Capua Carlo Candida, successor to Busca, obtained from Gregorio XVI the transport of the center to Rome, where the new Liutenant was plenipotentiary minister at the Holy See.

But there is also more a recently asserted reason that consolidates this memory in Ferrara. In 2004 and 2005 a recent purchase of the Cassa di Risparmio di Ferrara, has been loaned to an exhibition in Mantova: the work “ of a painter whose tie with our city has been of exceptional importance: Tiziano Vecellio direct heir of Giorgione” (as V. Lapierre wrote here in December 2004). It is the Portrait of Gabriele Tadino general

commander of the artillery of Carl V, knight and expert in the art of war, portraied with a golden necklace and the Jerolsolimitan cross Today in the series of twenty thousand stamps emitted from the Poste Magistrali del Sovrano Militare Ordine di Malta, the noble figure of that knight camps in a gallery the best and the more illustrious among its members.

Mona Hatoum

A lucid view of contemporary society deriving from a rigorous aesthetic research

Selecting an artist for the XIII edition of the Biennale Donna is an important and prestigious task. In choosing Mona Hatoum, one is presenting an artist whose work complements and completes the artistic and cultural themes of the previous two editions.

The choice of Mona Hatoum shows itself to be perfectly in line to bring to a close, without assuming to have done so exhaustively, such an interesting and revealing thematic quest. If one of the most examined aspects is nomadism and therefore cultural identity, then Hatoum is an excellent representative. There is no doubt that the cruel circumstances resulting from the outbreak of civil war in her native Lebanon prevented her from returning home; thereby strongly affecting her choices, but at the same time enriching and widening her artistic training and her socio-political development.

Like all exiles, she was able to look back objectively at her roots, but more importantly, this distance also made her look forward towards a different future. It may be that this loss of her past and her future is the origin of the redeeming “cynicism” that causes her to focus on the foibles of a contemporary society that is constantly floundering between scientific pragmatism and the iniquity of war. Between 1975 and 1981, Mona Hatoum lived in London where she attended first the Byam Shaw School of Art and then the Slade School of Art. She now divides her time betweenLondon and Berlin.

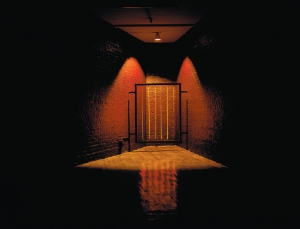

Mona Hatoum’s work shows obvious ties with minimalism and conceptual art, but exclusively as cultural background, while her style, language, and themes are absolutely her own, personal and strongly enthralling. Many of her works have an undercurrent that is insidiously hostile, provoking profound anguished reflection in the viewer. We soon realize that what we are seeing has differing values, varying significances, multiple interpretations. The Light at the End (1989) brings this home to us.

In a semi-dark corner are six incandescent metal bars, positioned vertically, perhaps the bars of a prison, or perhaps just an impenetrable area. The artist makes ambiguity her “weapon” of choice and uses it to catch you unaware, to strip away certainty, to derail, to cause unease. Her works certainly don’t want to be consolatory, in spite of the materials, shapes and colours that she uses to create her installations, sculptures and large scale objects. The objects that make up her works, stripped of their normal functions, resonate strongly with a formal elegance derived from a conscious aesthetic quest that is both sophisticated and piercing, fascinating and seductive, yet disconcerting and disorientating. In some of her larger works one perceives the intention to transmit the uncertainty coming from an emotional experience dominated by a fear as intense as the existential condition. In today’s world, we all have to live with this fear.

In the Eighties, Hatoum’s work focussed on performance and video pieces that sharply highlight the centrality and significance of the body. In 1985, she carried out a performance, Roadworks, in which she walked barefoot through the London neighbourhood of Brixton in bare feet dragging a pair of boots tied to her ankles with the effect of the awkward gait of a prisoner with chained feet. Much later I learnt that the performance wasn’t referring to prisoners, but rather to the Brixton Race Riots of 1981, highlighting the insecurity and the vulnerability that ordinary people faced during the conflict. Being able to read each artistic action, each work, not in an unequivocal way in which a definitive interpretation is pinned down, but in a more interactive way that results in multiplicity of readings and impressions is what gives Mona Hatoum’s work its appeal. Mona Hatoum used video surveillance cameras to film her first videos, possibly drawn by the ambiguous meaning of the word “surveillance.” In fact, in Italian, the dictionary defines it thus: Sorveglianza [Surveillance]: close direct observation with the aim of protecting or keeping and safeguarding, whereas the term Sorvegliato [Under observation] has a variety of meanings including “a person subjected to special measures of control by the police;” once again emphasizing the ambiguity implicit in the language which society and institutional power use to guard us.

In 1994, Mona Hatoum made a video, which is certainly disturbing, but revealing. With an endoscopic camera, a medical device, she decided to explore-survey the insides of her own body. The title of the video is Corps étranger. The fact that we are seeing her own body makes us uneasy, but then comes the spontaneous thought that none of us is familiar with the insides of our own bodies and this disquieting thought catches us by surprise. In some way, our own bodies are also foreign. The internal organs of one human body are not distinguishable on a formal aesthetic plane, in fact, the success of organ transplants is dependent upon genetic compatibility which has nothing to do with race, culture, religion, ideology, or membership in a clan or tribe. This lack of distinction of our entrails, foreign yet familiar territory, as Mona Hatoum calls it, made me think of the dramatic pictures of the black market for organs, which hurts the poorest populations most. Hatoum made another video of a completely different kind, but it equally moved me, called Measures of Distances (1988).

Here, we can glimpse the naked body of the artist’s mother as she is taking a shower, talking all the while. Across the screen, the Arabic script of her letters to her daughter fade in and out. As we watch, we hear the artist’s voice read these letters aloud in English, emphasizing the intimate, almost mystical, atmosphere, yet provoking a feeling that is mostly embarrassment, as though we have intruded. A new work, Nature morte aux grenades, is on show in this exhibition for the first time. This work is part of an ongoing aesthetic quest in which the functional use of daily objects is purposefully distorted. Objects that when deliberately enlarged lose their usual familiarity and assume a role that is sometimes stupefying, but also aggressive, hostile, tense, probably as much as to intimidate you into thinking again about their form and function. Nothing, or nearly nothing, is really as we would like it to be or as it should be ethically. Manipulation is always possible and most of the time dangerous. Be warned!

Città a misura di bambino

Gli interventi della Fondazione e dell'Amministrazione comunale a favore dei giovanissimi.

Gli interventi della Fondazione e dell'Amministrazione comunale a favore dei giovanissimi.

I problemi del rapporto del bambino con la città hanno una lunga storia e prendono consistenza operativa, dopo una lunga elaborazione teorica, con il convegno Una politica grande per i più piccoli tenutosi a Bologna nel 1990.

In quella sede si è evidenziato come fossero necessarie strutture dove il bambino potesse passare alcune ore della sua giornata in compagnia di coetanei, ma anche di genitori e nonni, intrattenuto su mille temi relativi al gioco e al lavoro da esperti pedagogisti, mentre gli adulti partecipavano alle attività dei bambini o familiarizzavano tra loro.

Si è riscontrato che così operando la formazione del carattere e della personalità si conduceva secondo più equilibrati parametri, con un arricchimento notevole anche della formazione degli adulti accompagnatori i quali sono, alla fine, i maggiori responsabili del processo educativo del figlio o del nipote.

Boldini: Works on Paper

Sixty-two years have gone by since Cesare Brandi set up, in the Benvenuto Tisi da Garofalo Hall of the Palazzo dei Diamanti, the original nucleus of the Museo Giovanni Boldini, thus adopting the museological criterion that Giuseppe Agnelli had suggested to the Fascist governor of Ferrara, Renzo Ravenna, as early as 1931.

Forty years later, the municipal and regional authorities of Ferrara successfully negotiated with Emilio Cardona the purchase of another part of the great Ferrarese's collection, considerably enriching the original nucleus of the Museo Boldini and making it the most important concentration of the master's work in existence: about 1700 items including oil paintings, water colours, pastels, drawings, sketches, engravings and personal effects belonging to the artist. But that material has never been wholly catalogued or photographed, nor has a general catalogue of the collection ever been published.

The "Ottava d'Oro"

Some months ago, one sunny afternoon in Ferrara, I took corso Porta Mare as far as Parco Massari. Once there, I stood gazing at it from the outside. A far different sight to when I was a boy. In those days the park belonged to the Massari dukes, who also owned the adjacent palazzo and a great deal of land in the Ferrara area. The gate was closed and no one could go in. That tangle of greenery without a sign of life was a formidable spur to the imagination.

A vocation for modern art

Giuseppe Pianori, a wealthy agriculturalist, rich but unostentatious, knows the end is drawing near, and on the 24th of March 1980 he goes to his lawyer and entrusts him with his secret will.

On the 12th of May that year, he passes away, and three days later, on the 15th of May, the said will is opened and published. To honour the memory of the the Pianori family in an appropriate and lasting manner, I intend to create and I do hereby create the "Giuseppe Pianori" foundation, with a view to developing and enriching the artistic and cultural heritage of Ferrara through the acquisition of works of modern art for the city's Civic Gallery of Modern Art, with a focus on works by Ferrarese artists who have made a significant contribution to the history of Italian art.